WSJ: Fed Prepares review for Central Bank Digital Currency

“WASHINGTON—The Federal Reserve plans as early as this week to launch a review of the potential benefits and risks of issuing a U.S. digital currency, as central banks around the world experiment with the potential new form of money.

Fed officials are divided on the matter, making it unlikely they will decide any time soon on whether to create a digital dollar. Unlike private cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, a Fed version would be issued by and backed by the U.S. central bank, a government entity, as are U.S. paper dollar bills and coins.

Advocates say a Fed digital dollar could make it faster and cheaper to move money around the financial system, bring into it people who lack bank accounts and provide an efficient way for the government to distribute financial aid.

Another motivating consideration: keeping up with other major jurisdictions considering a digital currency for domestic and international payments, Fed. Gov. Lael Brainard said in remarks before the National Association for Business Economics on Sept. 27.

“It’s just very hard for me to imagine that the U.S., given the status of the dollar as a dominant currency in international payments, wouldn’t come to the table in that circumstance with a similar kind of an offering,” she said.

However, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has indicated he sees reason for caution. He said last month it is more important to get the digital dollar right than to be first to market, in part because of the dollar’s critical global role.

He and other Fed officials have said the Fed’s research is early and exploratory. He said at a Sept. 22 press conference that they would only consider issuing a so-called central bank digital currency—or CBDC—if they believed there were “clear and tangible benefits that outweigh any costs and risks.”

Mr. Powell has pointed to other challenges, noting many Americans actively use and prefer cash. He also said there are privacy issues that would need to be addressed, since a Fed CBDC system would in theory allow the central bank to see what every user did with the currency.

“It’s our obligation to do the work both on technology and on public policy to form a basis for making an informed decision,” he said last month.

Randal Quarles, the central bank’s pointman on financial regulation, has voiced more skepticism about the need for a Fed digital currency. He said this summer that the U.S. dollar is already “highly digitized” and expressed doubts that a Fed CBDC would help draw people without bank accounts into the financial system—a goal that can be accomplished through other means, he said.

“Before we get carried away with the novelty, I think we need to subject the promises of a CBDC to a careful critical analysis,” he said, speaking at an event hosted by the Utah Bankers Association.

A Philadelphia Fed report warned that a U.S. central bank CBDC could destabilize the financial system in a crisis if people pull their money out of banks, mutual funds, stocks and other investments and plow it into the Fed’s ultrasafe currency.

Some banks—facing the prospect of competition from the Fed for deposits—have already signaled they don’t believe it has the legal authority to issue a digital currency without authorization from Congress.

The Fed plans to launch the review by releasing a paper analyzing the issue and seeking public comment, but it is unlikely to include a firm policy recommendation.

Next, the Boston Fed, working with researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is expected to release a more-technical paper outlining how a digital dollar might work.

In theory, a Fed digital dollar could be used alongside traditional paper money, but many of the details of how exactly people would access digital dollars, and how they would fit into the financial system, are unclear.

For instance, the Fed would have to decide whether consumers would access their digital dollars with accounts directly at the central bank or through existing commercial lenders, said Richard Levin, chair of the fintech and regulation practice at Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough LLP.

Some advocates say CBDCs could help improve the effectiveness of monetary policy by allowing a central bank to change interest rates directly on accounts holding CBDCs. This could allow central banks to bypass often fickle financial markets and bring monetary policy right to the retail level.

The Fed paper comes as central banks around the world contend with the rise of numerous private electronic alternatives to traditional money and weigh creating their own versions. Private offerings of digital currencies have been extremely volatile, and in many cases have been associated with criminal activities and have so far failed to be adopted widely for daily transactions, such as for buying groceries or movie tickets.

China created its own government-issued digital currency earlier this year and recently prohibited transactions using cryptocurrencies issued by nonmonetary authorities, naming bitcoin, ether and tether as examples. El Salvador, meanwhile, became the first country in the world to adopt bitcoin as a national currency alongside the U.S. dollar.”

NY Times: The Scientist and the A.I.-Assisted, Remote-Control Killing Machine

SECTIONSSEARCHSKIP TO CONTENTSKIP TO SITE INDEXMIDDLE EAST

The Scientist and the A.I.-Assisted, Remote-Control Killing Machine

Israeli agents had wanted to kill Iran’s top nuclear scientist for years. Then they came up with a way to do it with no operatives present.

By Ronen Bergman and Farnaz FassihiSept. 18, 2021Updated 9:58 a.m. ETRead in Persian

Iran’s top nuclear scientist woke up an hour before dawn, as he did most days, to study Islamic philosophy before his day began.

That afternoon, he and his wife would leave their vacation home on the Caspian Sea and drive to their country house in Absard, a bucolic town east of Tehran, where they planned to spend the weekend.

Iran’s intelligence service had warned him of a possible assassination plot, but the scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, had brushed it off.

Convinced that Mr. Fakhrizadeh was leading Iran’s efforts to build a nuclear bomb, Israel had wanted to kill him for at least 14 years. But there had been so many threats and plots that he no longer paid them much attention.

Despite his prominent position in Iran’s military establishment, Mr. Fakhrizadeh wanted to live a normal life. He craved small domestic pleasures: reading Persian poetry, taking his family to the seashore, going for drives in the countryside.

And, disregarding the advice of his security team, he often drove his own car to Absard instead of having bodyguards drive him in an armored vehicle. It was a serious breach of security protocol, but he insisted.

So shortly after noon on Friday, Nov. 27, he slipped behind the wheel of his black Nissan Teana sedan, his wife in the passenger seat beside him, and hit the road.

Caspian Sea

By Jugal K. Patel

An Elusive Target

Since 2004, when the Israeli government ordered its foreign intelligence agency, the Mossad, to prevent Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons, the agency had been carrying out a campaign of sabotage and cyberattacks on Iran’s nuclear fuel enrichment facilities. It was also methodically picking off the experts thought to be leading Iran’s nuclear weapons program.

Since 2007, its agents had assassinated five Iranian nuclear scientists and wounded another. Most of the scientists worked directly for Mr. Fakhrizadeh (pronounced fah-KREE-zah-deh) on what Israeli intelligence officials said was a covert program to build a nuclear warhead, including overcoming the substantial technical challenges of making one small enough to fit atop one of Iran’s long-range missiles.

Israeli agents had also killed the Iranian general in charge of missile development and 16 members of his team.ImageOne of the most difficult challenges for Iran was to build a nuclear warhead small enough to fit atop a long-range missile like the one seen in a military parade in Tehran in 2018.Credit…Abedin Taherkenareh/EPA, via Shutterstock

But the man Israel said led the bomb program was elusive.

In 2009, a hit team was waiting for Mr. Fakhrizadeh at the site of a planned assassination in Tehran, but the operation was called off at the last moment. The plot had been compromised, the Mossad suspected, and Iran had laid an ambush.

This time they were going to try something new.

Iranian agents working for the Mossad had parked a blue Nissan Zamyad pickup truck on the side of the road connecting Absard to the main highway. The spot was on a slight elevation with a view of approaching vehicles. Hidden beneath tarpaulins and decoy construction material in the truck bed was a 7.62-mm sniper machine gun.

Around 1 p.m., the hit team received a signal that Mr. Fakhrizadeh, his wife and a team of armed guards in escort cars were about to leave for Absard, where many of Iran’s elite have second homes and vacation villas.

The assassin, a skilled sniper, took up his position, calibrated the gun sights, cocked the weapon and lightly touched the trigger.

He was nowhere near Absard, however. He was peering into a computer screen at an undisclosed location many hundreds of miles away. The entire hit squad had already left Iran.

Reports of a Killing

The news reports from Iran that afternoon were confusing, contradictory and mostly wrong.

A team of assassins had waited alongside the road for Mr. Fakhrizadeh to drive by, one report said. Residents heard a big explosion followed by intense machine gun fire, said another. A truck exploded ahead of Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s car, then five or six gunmen jumped out of a nearby car and opened fire. A social media channel affiliated with the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps reported an intense gun battle between Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s bodyguards and as many as a dozen attackers. Several people were killed, witnesses said.

One of the most far-fetched accounts emerged a few days later.ImageMr. Fakhrizadeh’s Nissan Teana and blood on the road after the attack on Nov. 27, 2020.Credit…Wana News Agency, via Reuters

Several Iranian news organizations reported that the assassin was a killer robot, and that the entire operation was conducted by remote control. These reports directly contradicted the supposedly eyewitness accounts of a gun battle between teams of assassins and bodyguards and reports that some of the assassins had been arrested or killed.

Iranians mocked the story as a transparent effort to minimize the embarrassment of the elite security force that failed to protect one of the country’s most closely guarded figures.

“Why don’t you just say Tesla built the Nissan, it drove by itself, parked by itself, fired the shots and blew up by itself?” one hard-line social media account said.

Thomas Withington, an electronic warfare analyst, told the BBC that the killer robot theory should be taken with “a healthy pinch of salt,” and that Iran’s description appeared to be little more than a collection of “cool buzzwords.”

Except this time there really was a killer robot.

The straight-out-of-science-fiction story of what really happened that afternoon and the events leading up to it, published here for the first time, is based on interviews with American, Israeli and Iranian officials, including two intelligence officials familiar with the details of the planning and execution of the operation, and statements Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s family made to the Iranian news media.

The operation’s success was the result of many factors: serious security failures by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, extensive planning and surveillance by the Mossad, and an insouciance bordering on fatalism on the part of Mr. Fakhrizadeh.

But it was also the debut test of a high-tech, computerized sharpshooter kitted out with artificial intelligence and multiple-camera eyes, operated via satellite and capable of firing 600 rounds a minute.

The souped-up, remote-controlled machine gun now joins the combat drone in the arsenal of high-tech weapons for remote targeted killing. But unlike a drone, the robotic machine gun draws no attention in the sky, where a drone could be shot down, and can be situated anywhere, qualities likely to reshape the worlds of security and espionage.

‘Remember That Name’

Preparations for the assassination began after a series of meetings toward the end of 2019 and in early 2020 between Israeli officials, led by the Mossad director, Yossi Cohen, and high-ranking American officials, including President Donald J. Trump, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and the C.I.A. director, Gina Haspel.ImageThe Mossad director, Yossi Cohen, presented Israel’s plans to President Donald J. Trump, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and the C.I.A. director, Gina Haspel.Credit…Amir Cohen/Reuters

Israel had paused the sabotage and assassination campaign in 2012, when the United States began negotiations with Iran leading to the 2015 nuclear agreement. Now that Mr. Trump had abrogated that agreement, the Israelis wanted to resume the campaign to try to thwart Iran’s nuclear progress and force it to accept strict constraints on its nuclear program.

In late February, Mr. Cohen presented the Americans with a list of potential operations, including the killing of Mr. Fakhrizadeh. Mr. Fakhrizadeh had been at the top of Israel’s hit list since 2007, and the Mossad had never taken its eyes off him.

In 2018, Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, held a news conference to show off documents the Mossad had stolen from Iran’s nuclear archives. Arguing that they proved that Iran still had an active nuclear weapons program, he mentioned Mr. Fakhrizadeh by name several times.

“Remember that name,” he said. “Fakhrizadeh.”

The American officials briefed about the assassination plan in Washington supported it, according to an official who was present at the meeting.

Both countries were encouraged by Iran’s relatively tepid response to the American assassination of Maj. Gen. Qassim Suleimani, the Iranian military commander killed in a U.S. drone strike with the help of Israeli intelligence in January 2020. If they could kill Iran’s top military leader with little blowback, it signaled that Iran was either unable or reluctant to respond more forcefully.

The surveillance of Mr. Fakhrizadeh moved into high gear.

As the intelligence poured in, the difficulty of the challenge came into focus: Iran had also taken lessons from the Suleimani killing, namely that their top officials could be targeted. Aware that Mr. Fakhrizadeh led Israel’s most-wanted list, Iranian officials had locked down his security.

His security details belonged to the elite Ansar unit of the Revolutionary Guards, heavily armed and well trained, who communicated via encrypted channels. They accompanied Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s movements in convoys of four to seven vehicles, changing the routes and timing to foil possible attacks. And the car he drove himself was rotated among four or five at his disposal.ImageMemorials at the Baghdad airport, where Maj. Gen. Qassim Suleimani was killed. The Suleimani killing offered lessons for both Israel and Iran.Credit…Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

Israel had used a variety of methods in the earlier assassinations. The first nuclear scientist on the list was poisoned in 2007. The second, in 2010, was killed by a remotely detonated bomb attached to a motorcycle, but the planning had been excruciatingly complex, and an Iranian suspect was caught. He confessed and was executed.

After that debacle, the Mossad switched to simpler, in-person killings. In each of the next four assassinations, from 2010 to 2012, hit men on motorcycles sidled up beside the target’s car in Tehran traffic and either shot him through the window or attached a sticky-bomb to the car door, then sped off.

But Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s armed convoy, on the lookout for such attacks, made the motorcycle method impossible.

The planners considered detonating a bomb along Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s route, forcing the convoy to a halt so it could be attacked by snipers. That plan was shelved because of the likelihood of a gangland-style gun battle with many casualties.

The idea of a pre-positioned, remote-controlled machine gun was proposed, but there were a host of logistical complications and myriad ways it could go wrong. Remote-controlled machine guns existed and several armies had them, but their bulk and weight made them difficult to transport and conceal, and they had only been used with operators nearby.

Time was running out.

By the summer, it looked as if Mr. Trump, who saw eye to eye on Iran with Mr. Netanyahu, could lose the American election. His likely successor, Joseph R. Biden Jr., had promised to reverse Mr. Trump’s policies and return to the 2015 nuclear agreement that Israel had vigorously opposed.ImagePresident Donald J. Trump and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at the White House in September 2020. Israel wanted to act while Mr. Trump was still in office.Credit…Doug Mills/The New York Times

If Israel was going to kill a top Iranian official, an act that had the potential to start a war, it needed the assent and protection of the United States. That meant acting before Mr. Biden could take office. In Mr. Netanyahu’s best-case scenario, the assassination would derail any chance of resurrecting the nuclear agreement even if Mr. Biden won.

The Scientist

Mohsen Fakhrizadeh grew up in a conservative family in the holy city of Qom, the theological heart of Shia Islam. He was 18 when the Islamic revolution toppled Iran’s monarchy, a historical reckoning that fired his imagination.

He set out to achieve two dreams: to become a nuclear scientist and to take part in the military wing of the new government. As a symbol of his devotion to the revolution, he wore a silver ring with a large, oval red agate, the same type worn by Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and by General Suleimani.

He joined the Revolutionary Guards and climbed the ranks to general. He earned a Ph.D. in nuclear physics from Isfahan University of Technology with a dissertation on “identifying neutrons,” according to Ali Akbar Salehi, the former head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Agency and a longtime friend and colleague.

He led the missile development program for the Guards and pioneered the country’s nuclear program. As research director for the Defense Ministry, he played a key role in developing homegrown drones and, according to two Iranian officials, traveled to North Korea to join forces on missile development. At the time of his death, he was deputy defense minister.

“In the field of nuclear and nanotechnology and biochemical war, Mr. Fakhrizadeh was a character on par with Qassim Suleimani but in a totally covert way,” Gheish Ghoreishi, who has advised Iran’s Foreign Ministry on Arab affairs, said in an interview.

When Iran needed sensitive equipment or technology that was prohibited under international sanctions, Mr. Fakhrizadeh found ways to obtain them.ImagePresident Hassan Rouhani, second from left, visiting an exhibition in Tehran on Iran’s nuclear program in April.Credit…Office of the Iranian Presidency, via Associated Press

“He had created an underground network from Latin America to North Korea and Eastern Europe to find the parts that we needed,” Mr. Ghoreishi said.

Mr. Ghoreishi and a former senior Iranian official said that Mr. Fakhrizadeh was known as a workaholic. He had a serious demeanor, demanded perfection from his staff and had no sense of humor, they said. He seldom took time off. And he eschewed media attention.

Most of his professional life was top secret, better known to the Mossad than to most Iranians.

His career may have been a mystery even to his children. His sons said in a television interview that they had tried to piece together what their father did based on his sporadic comments. They said they had guessed that he was involved in the production of medical drugs.

When international nuclear inspectors came to call, they were told that he was unavailable, his laboratories and testing grounds off limits. Concerned about Iran’s stonewalling, the United Nations Security Council froze Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s assets as part of a package of sanctions on Iran in 2006.

Although he was considered the father of Iran’s nuclear program, he never attended the talks leading to the 2015 agreement.

The black hole that was Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s career was a major reason that even when the agreement was completed, questions remained about whether Iran still had a nuclear weapons program and how far along it was.

Iran has steadfastly insisted that its nuclear program was for purely peaceful purposes and that it had no interest in developing a bomb. Ayatollah Khamenei had even issued an edict declaring that such a weapon would violate Islamic law.

But investigators with the International Atomic Energy Agency concluded in 2011 that Iran had “carried out activities relevant to the development of a nuclear device.” They also said that while Iran had dismantled its focused effort to build a bomb in 2003, significant work on the project had continued.ImagePosters in Tehran honoring national heroes and martyrs. Mr. Fakhrizadeh, left, was relatively unknown, while General Suleimani was famous.Credit…Atta Kenare/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

According to the Mossad, the bomb-building program had simply been deconstructed and its component parts scattered among different programs and agencies, all under Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s direction.

In 2008, when President George W. Bush was visiting Jerusalem, Prime Minister Ehud Olmert played him a recording of a conversation Israeli officials said took place a short time before between a man they identified as Mr. Fakhrizadeh and a colleague. According to three people who say they heard the recording, Mr. Fakhrizadeh spoke explicitly about his ongoing effort to develop a nuclear warhead.

A spokesman for Mr. Bush did not reply to a request for comment. The New York Times could not independently confirm the existence of the recording or its contents.

Programming a Hit

A killer robot profoundly changes the calculus for the Mossad.

The organization has a longstanding rule that if there is no rescue, there is no operation, meaning a foolproof plan to get the operatives out safely is essential. Having no agents in the field tips the equation in favor of the operation.

But a massive, untested, computerized machine gun presents a string of other problems.

The first is how to get the weapon in place.

Israel chose a special model of a Belgian-made FN MAG machine gun attached to an advanced robotic apparatus, according to an intelligence official familiar with the plot. The official said the system was not unlike the off-the-rack Sentinel 20 manufactured by the Spanish defense contractor Escribano.

But the machine gun, the robot, its components and accessories together weigh about a ton. So the equipment was broken down into its smallest possible parts and smuggled into the country piece by piece, in various ways, routes and times, then secretly reassembled in Iran.

The robot was built to fit in the bed of a Zamyad pickup, a common model in Iran. Cameras pointing in multiple directions were mounted on the truck to give the command room a full picture not just of the target and his security detail, but of the surrounding environment. Finally, the truck was packed with explosives so it could be blown to bits after the kill, destroying all evidence.

There were further complications in firing the weapon. A machine gun mounted on a truck, even a parked one, will shake after each shot’s recoil, changing the trajectory of subsequent bullets.ImageIsrael used a special model of a Belgian-made FN MAG machine gun, similar to this one, attached to a robotic apparatus.Credit…Darron Mark/Corbis, via Getty Images

Also, even though the computer communicated with the control room via satellite, sending data at the speed of light, there would be a slight delay: What the operator saw on the screen was already a moment old, and adjusting the aim to compensate would take another moment, all while Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s car was in motion.

The time it took for the camera images to reach the sniper and for the sniper’s response to reach the machine gun, not including his reaction time, was estimated to be 1.6 seconds, enough of a lag for the best-aimed shot to go astray.

The A.I. was programmed to compensate for the delay, the shake and the car’s speed.

Another challenge was to determine in real time that it was Mr. Fakhrizadeh driving the car and not one of his children, his wife or a bodyguard.

Israel lacks the surveillance capabilities in Iran that it has in other places, like Gaza, where it uses drones to identify a target before a strike. A drone large enough to make the trip to Iran could be easily shot down by Iran’s Russian-made antiaircraft missiles. And a drone circling the quiet Absard countryside could expose the whole operation.

The solution was to station a fake disabled car, resting on a jack with a wheel missing, at a junction on the main road where vehicles heading for Absard had to make a U-turn, some three quarters of a mile from the kill zone. That vehicle contained another camera.

At dawn Friday, the operation was put into motion. Israeli officials gave the Americans a final heads up.

The blue Zamyad pickup was parked on the shoulder of Imam Khomeini Boulevard. Investigators later found that security cameras on the road had been disabled.

The Drive

As the convoy left the city of Rostamkala on the Caspian coast, the first car carried a security detail. It was followed by the unarmored black Nissan driven by Mr. Fakhrizadeh, with his wife, Sadigheh Ghasemi, at his side. Two more security cars followed.

The security team had warned Mr. Fakhrizadeh that day of a threat against him and asked him not to travel, according to his son Hamed Fakhrizadeh and Iranian officials.

But Mr. Fakhrizadeh said he had a university class to teach in Tehran the next day, his sons said, and he could not do it remotely.

Ali Shamkhani, the secretary of Supreme National Council, later told the Iranian media that intelligence agencies even had knowledge of the possible location of an assassination attempt, though they were uncertain of the date.

The Times could not verify whether they had such specific information or whether the claim was an effort at damage control after an embarrassing intelligence failure.

Iran had already been shaken by a series of high-profile attacks in recent months that in addition to killing leaders and damaging nuclear facilities made it clear that Israel had an effective network of collaborators inside Iran.

The recriminations and paranoia among politicians and intelligence officials only intensified after the assassination. Rival intelligence agencies — under the Ministry of Intelligence and the Revolutionary Guards — blamed each other.ImageMembers of the Revolutionary Guards in Tehran in 2018. A special unit of the Guards was in charge of Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s security.Credit…Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

A former senior Iranian intelligence official said that he heard that Israel had even infiltrated Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s security detail, which had knowledge of last-minute changes to his movement, the route and the time.

But Mr. Shamkhani said there had been so many threats over the years that Mr. Fakhrizadeh did not take them seriously.

He refused to ride in an armored car and insisted on driving one of his cars himself. When he drove with his wife, he would ask the bodyguards to drive a separate car behind him instead of riding with them, according to three people familiar with his habits.

Mr. Fakhrizadeh may have also found the idea of martyrdom attractive.

“Let them kill,” he said in a recording Mehr News, a conservative outlet, published in November. “Kill as much as they want, but we won’t be grounded. They’ve killed scientists, so we have hope to become a martyr even though we don’t go to Syria and we don’t go to Iraq.”

Even if Mr. Fakhrizadeh accepted his fate, it was not clear why the Revolutionary Guards assigned to protect him went along with such blatant security lapses. Acquaintances said only that he was stubborn and insistent.

If Mr. Fakhrizadeh had been sitting in the rear, it would have been much harder to identify him and to avoid killing anyone else. If the car had been armored and the windows bulletproofed, the hit squad would have had to use special ammunition or a powerful bomb to destroy it, making the plan far more complicated.

The Strike

Shortly before 3:30 p.m., the motorcade arrived at the U-turn on Firuzkouh Road. Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s car came to a near halt, and he was positively identified by the operators, who could also see his wife sitting beside him.

By Jugal K. Patel

The convoy turned right on Imam Khomeini Boulevard, and the lead car then zipped ahead to the house to inspect it before Mr. Fakhrizadeh arrived. Its departure left Mr. Fakhrizadeh’s car fully exposed.

The convoy slowed down for a speed bump just before the parked Zamyad. A stray dog began crossing the road.

The machine gun fired a burst of bullets, hitting the front of the car below the windshield. It is not clear if these shots hit Mr. Fakhrizadeh but the car swerved and came to a stop.

The shooter adjusted the sights and fired another burst, hitting the windshield at least three times and Mr. Fakhrizadeh at least once in the shoulder. He stepped out of the car and crouched behind the open front door.ImageImam Khomeini Boulevard in Absard after the assassination.Credit…Fars News Agency, via Associated Press

According to Iran’s Fars News, three more bullets tore into his spine. He collapsed on the road.

The first bodyguard arrived from a chase car: Hamed Asghari, a national judo champion, holding a rifle. He looked around for the assailant, seemingly confused.

Ms. Ghasemi ran out to her husband. “They want to kill me and you must leave,” he told her, according to his sons.

She sat on the ground and held his head on her lap, she told Iranian state television.

The blue Zamyad exploded.

That was the only part of the operation that did not go as planned.

The explosion was intended to rip the robot to shreds so the Iranians could not piece together what had happened. Instead, most of the equipment was hurled into the air and then fell to the ground, damaged beyond repair but largely intact.

The Revolutionary Guards’ assessment — that the attack was carried out by a remote-controlled machine gun “equipped with an intelligent satellite system” using artificial intelligence — was correct.

The entire operation took less than a minute. Fifteen bullets were fired.

Iranian investigators noted that not one of them hit Ms. Ghasemi, seated inches away, accuracy that they attributed to the use of facial recognition software.

Hamed Fakhrizadeh was at the family home in Absard when he received a distress call from his mother. He arrived within minutes to what he described as a scene of “full-on war.” Smoke and fog clouded his vision, and he could smell blood.

“It was not a simple terrorist attack for someone to come and fire a bullet and run,” he said later on state television. “His assassination was far more complicated than what you know and think. He was unknown to the Iranian public, but he was very well known to those who are the enemy of Iran’s development.”

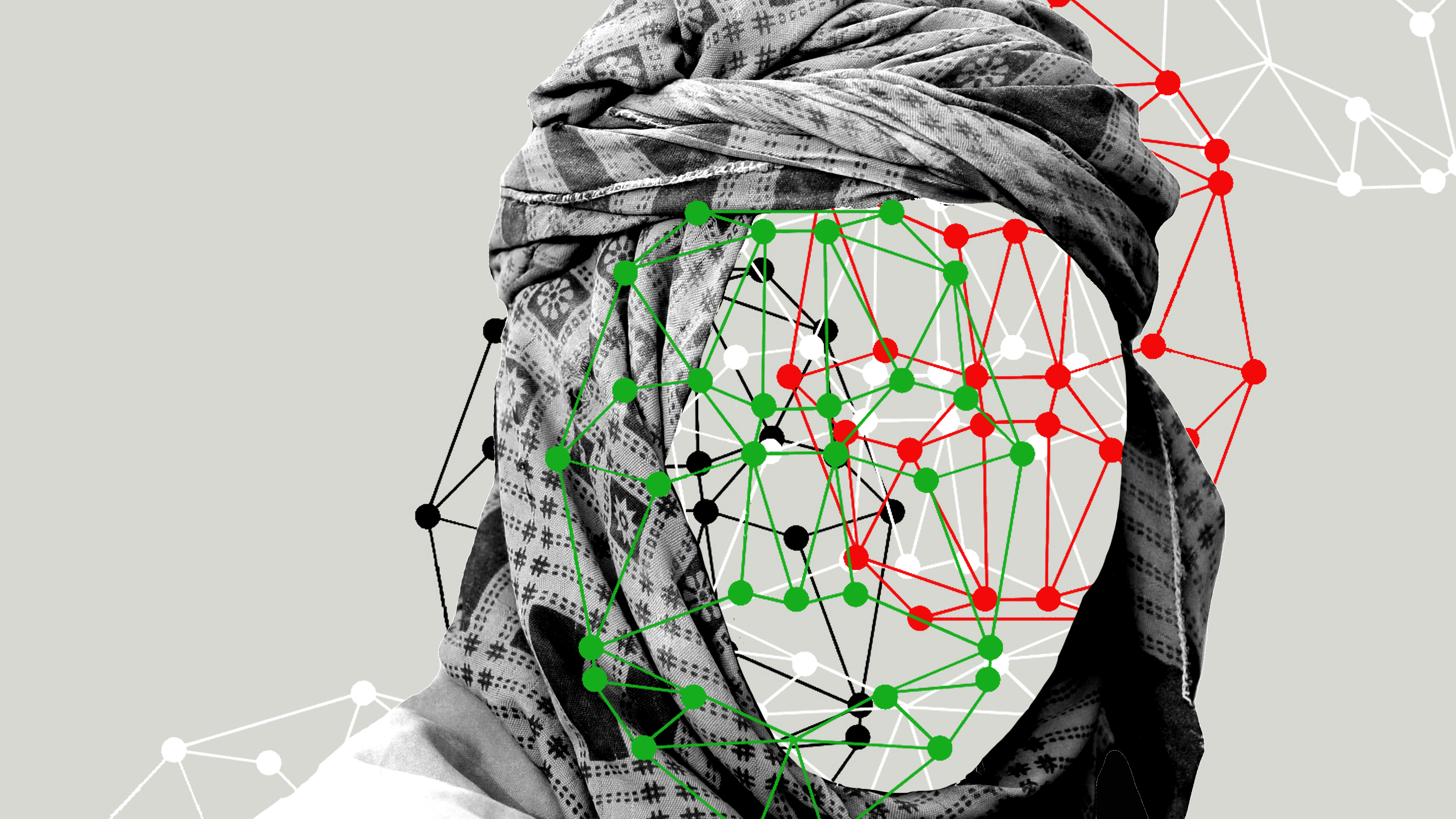

Tech Review: Real story of Biometrics in Afghanistan

“This is the real story of the Afghan biometric databases abandoned to the Taliban

By capturing 40 pieces of data per person—from iris scans and family links to their favorite fruit—a system meant to cut fraud in the Afghan security forces may actually aid the Taliban.by

August 30, 2021 ANDREA DAQUINO

ANDREA DAQUINO

As the Taliban swept through Afghanistan in mid-August, declaring the end of two decades of war, reports quickly circulated that they had also captured US military biometric devices used to collect data such as iris scans, fingerprints, and facial images. Some feared that the machines, known as HIIDE, could be used to help identify Afghans who had supported coalition forces.

According to experts speaking to MIT Technology Review, however, these devices actually provide only limited access to biometric data, which is held remotely on secure servers. But our reporting shows that there is a greater threat from Afghan government databases containing sensitive personal information that could be used to identify millions of people around the country.

MIT Technology Review spoke to two individuals familiar with one of these systems, a US-funded database known as APPS, the Afghan Personnel and Pay System. Used by both the Afghan Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Defense to pay the national army and police, it is arguably the most sensitive system of its kind in the country, going into extreme levels of detail about security personnel and their extended networks. We granted the sources anonymity to protect them against potential reprisals.

Related Story

Afghans are being evacuated via WhatsApp, Google Forms, or by any means possible

The only hope for many caught by the Taliban takeover is a chaotic and sometimes risky online volunteer response.

Started in 2016 to cut down on paycheck fraud involving fake identities, or “ghost soldiers,” APPS contains some half a million records about every member of the Afghan National Army and Afghan National Police, according to estimates by individuals familiar with the program. The data is collected “from the day they enlisted,” says one individual who worked on the system, and remains in the system forever, whether or not someone remains actively in service. Records could be updated, he added, but he was not aware of any deletion or data retention policy—not even in contingency situations, such as a Taliban takeover.

A presentation on the police recruitment process from NATO’s Combined Security Training Command–Afghanistan shows that just one of the application forms alone collected 36 data points. Our sources say that each profile in APPS holds at least 40 data fields.

These include obvious personal information such as name, date, and place of birth, as well as a unique ID number that connects each profile to a biometric profile kept by the Afghan Ministry of Interior.

But it also contains details on the individuals’ military specialty and career trajectory, as well as sensitive relational data such as the names of their father, uncles, and grandfathers, as well as the names of the two tribal elders per recruit who served as guarantors for their enlistment. This turns what was a simple digital catalogue into something far more dangerous, according to Ranjit Singh, a postdoctoral scholar at the nonprofit research group Data & Society who studies data infrastructures and public policy. He calls it a sort of “genealogy” of “community connections” that is “putting all of these people at risk.”

The information is also of deep military value—whether for the Americans who helped construct it or for the Taliban, both of which are “looking for networks” of their opponent’s supporters, says Annie Jacobsen, a journalist and author of First Platoon: A Story of Modern War in the Age of Identity Dominance.

But not all the data has such clear use. The police ID application form, for example, also appears to ask for recruits’ favorite fruit and vegetable. The Office of the Secretary of Defense referred questions about this information to United States Central Command, which did not respond to a request for comment on what they should do with such data.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if they looked at the databases and started printing lists … and are now head-hunting former military personnel.”

While asking about fruits and vegetables may feel out of place on a police recruitment form, it indicates the scope of the information being collected and, says Singh, points to two important questions: What data is legitimate to collect to achieve the state’s purpose, and is the balance between the benefits and drawbacks appropriate?

In Afghanistan, where data privacy laws were not written or enacted until years after the US military and its contractors began capturing biometric information, these questions never received clear answers.

The resulting records are extremely comprehensive.

“Give me a field that you think we will not collect, and I’ll tell you you’re wrong,” said one of the individuals involved.

Then he corrected himself: “I think we don’t have mothers’ names. Some people don’t like to share their mother’s name in our culture.”

A growing fear of reprisals

The Taliban have stated publicly that they will not carry out targeted retribution against Afghans who had worked with the previous government or coalition forces. But their actions—historically and since their takeover—have not been reassuring.

On August 24, the UN High Commissioner of Human Rights told a special G7 meeting that her office had received credible reports of “summary executions of civilians and combat members of the Afghan national security forces.”

“I wouldn’t be surprised if they looked at the databases and started printing lists based on this … and now are head-hunting former military personnel,” one individual familiar with the database told us.

Sign up for The Download

– Your daily dose of what’s up in emerging technologySign up

Stay updated on MIT Technology Review initiatives and events?

YesNo

An investigation by Amnesty International found that the Taliban tortured and massacred nine ethnic Hazara men after capturing Ghazni province in early July, while in Kabul there have been numerous reports of Taliban going door to door to “register” individuals who had worked for the government or internationally funded projects.

Biometrics have played a role in such activity going back to at least 2016, according to local media accounts. In one widely reported incident from that year, insurgents ambushed a bus en route to Kunduz and took 200 passengers hostage, eventually killing 12, including local Afghan National Army soldiers returning to their base after visiting family. Witnesses told local police at the time that the Taliban used some kind of fingerprint scanner to check people’s identities.

It’s unclear what kinds of devices these were, or whether they were the same ones used by American forces to help establish “identity dominance”—the Pentagon’s goal of knowing who people were and what they had done.

Related Story

The Taliban, not the West, won Afghanistan’s technological war

The US-led coalition had more firepower, more equipment, and more money. But it was the Taliban that gained most from technological progress.

US officials were particularly interested in tracking identities to disrupt networks of bomb makers, who were successfully evading detection as their deadly improvised explosive devices caused large numbers of casualties among American troops. With biometric devices, military personnel could capture people’s faces, eyes, and fingerprints—and use that unique, immutable data to connect individuals, like bomb makers, with specific incidents. Raw data tended to go one way—from devices back to a classified DOD database—while actionable information, such as lists of people to “be on the lookout for”, was downloaded back onto the devices.

Incidents like the one in Kunduz seemed to suggest that these devices could access broader sets of data, something that the Afghan Ministry of Defense and American officials alike have repeatedly denied.

“The U.S. has taken prudent actions to ensure that sensitive data does not fall into the Taliban’s hands. This data is not at risk of misuse. That’s unfortunately about all I can say,” wrote Eric Pahon, a Defense Department spokesperson, in an emailed statement shortly after publication.

“They should also have thought of securing it”

But Thomas Johnson, a research professor at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, provides another possible explanation for how the Taliban may have used biometric information in the Kunduz attack.

Instead of their taking the data straight from HIIDE devices, he told MIT Technology Review, it is possible that Taliban sympathizers in Kabul provided them with databases of military personnel against which they could verify prints. In other words, even back in 2016, it may have been the databases, rather than the devices themselves, that posed the greatest risk.

Regardless, some locals are convinced that the collection of their biometric information has put them in danger. Abdul Habib, 32, a former ANA soldier who lost friends in the Kunduz attack, blamed access to biometric data for their deaths. He was so concerned that he too could be identified by the databases, that he left the army—and Kunduz province—shortly after the bus attack.

When he spoke with MIT Technology Review shortly before the fall of Kabul, Habib had been living in the capital for five years, and working in the private sector.

“When it was first introduced, I was happy about this new biometric system,” he said. “I thought it was something useful and the army would benefit from it, but now looking back, I don’t think it was a good time to introduce something like that. If they are making such a system, they should also have thought of securing it.”

And even in Kabul, he added, he hasn’t felt safe: “A colleague was told that ‘we will remove your biometrics from the system,’ but as far as I know, once it is saved, then they can’t remove it.”

When we last spoke to him just before the August 31 withdrawal deadline, as tens of thousands of Afghans surrounded the Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul in attempts to leave on an evacuation flight, Habib said that he had made it in. His biometric data was compromised, but with any luck, he would be leaving Afghanistan.

What other databases exist?

APPS may be one of the most fraught systems in Afghanistan, but it is not unique—nor even the largest.

The Afghan government—with the support of its international donors—has embraced the possibilities of biometric identification. Biometrics would “help our Afghan partners understand who its citizens are … help Afghanistan control its borders; and … allow GIRoA [the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan] to have ‘identity dominance,’” as one American military official put it in a 2010 biometrics conference in Kabul.

Central to the effort was the Ministry of Interior’s biometric database, called the Afghan Automatic Biometric Identification System (AABIS), but often referred to simply as the Biometrics Center. AABIS itself was modeled after the highly classified Department of Defense biometric system called the Automatic Biometric Identification System, which helped identify targets for drone strikes.

Related Story

Afghans are being evacuated via WhatsApp, Google Forms, or by any means possible

The only hope for many caught by the Taliban takeover is a chaotic and sometimes risky online volunteer response.

According to Jacobsen’s book, AABIS aimed to cover 80% of the Afghan population by 2012, or roughly 25 million people. While there is no publicly available information on just how many records this database now contains, and neither the contractor managing the database nor officials from the US Defense Department have responded to requests for comment, one unconfirmed figure from the LinkedIn profile of its US-based program manager puts it at 8.1 million records.

AABIS was widely used in a variety of ways by the previous Afghan government. Applications for government jobs and roles at most projects required a biometric check from the MOI system to ensure that applicants had no criminal or terrorist background. Biometric checks were also required for passport, national ID, and driver’s license applications, as well as registrations for the country’s college entrance exam.

Another database, slightly smaller than AABIS, was connected to the “e-tazkira,” the country’s electronic national ID card. By the time the government fell, it had roughly 6.2 million applications in process, according to the National Statistics and Information Authority, though it is unclear how many applicants had already submitted biometric data.

Biometrics were also used—or at least publicized—by other government departments as well. The Independent Election Commission used biometric scanners in an attempt to prevent voter fraud during the 2019 parliamentary elections, with questionable results. In 2020, the Ministry of Commerce and Industries announced that it would collect biometrics from those who were registering new businesses.

Despite the plethora of systems, they were never fully connected to each other. An August 2019 audit by the US found that despite the $38 million spent to date, APPS had not met many of its aims: biometrics still weren’t integrated directly into its personnel files, but were just linked by the unique biometric number. Nor did the system connect directly to other Afghan government computer systems, like that of the Ministry of Finance, which sent out the salaries. APPS also still relied on manual data-entry processes, said the audit, which allowed room for human error or manipulation.

A global issue

Afghanistan is not the only country to embrace biometrics. Many countries are concerned about so-called “ghost beneficiaries”—fake identities that are used to illegally collect salaries or other funds. Preventing such fraud is a common justification for biometric systems, says Amba Kak, the director of global policy and programs at the AI Now institute and a legal expert on biometric systems.

“It’s really easy to paint this [APPS] as exceptional,” says Kak, who co-edited a book on global biometric policies. It “seems to have a lot of continuity with global experiences” around biometrics.

“Biometric ID as the only efficient means for legal identification is … flawed and a little dangerous.”

Amber Kak, AI Now

It’s widely recognized that having legal identification documents is a right, but “conflating biometric ID as the only efficient means for legal identification,” she says, is “flawed and a little dangerous.”

Kak questions whether biometrics—rather than policy fixes—are the right solution to fraud, and adds that they are often “not evidence-based.”

But driven largely by US military objectives and international funding, Afghanistan’s rollout of such technologies has been aggressive. Even if APPS and other databases had not yet achieved the level of function they were intended to, they still contain many terabytes of data on Afghan citizens that the Taliban can mine.

“Identity dominance”—but by whom?

The growing alarm over the biometric devices and databases left behind, and the reams of other data about ordinary life in Afghanistan, has not stopped the collection of people’s sensitive data in the two weeks between the Taliban’s entry into Kabul and the official withdrawal of American forces.

This time, the data is being collected mostly by well-intentioned volunteers in unsecured Google forms and spreadsheets, highlighting either that the lessons on data security have not yet been learned—or that they must be relearned by every group involved.

Singh says the issue of what happens to data during conflicts or governmental collapse needs to be given more attention. “We don’t take it seriously,” he says, “But we should, especially in these war-torn areas where information can be used to create a lot of havoc.”

Kak, the biometrics law researcher, suggests that perhaps the best way to protect sensitive data would be if “these kinds of [data] infrastructures … weren’t built in the first place.”

For Jacobsen, the author and journalist, it is ironic that the Department of Defense’s obsession with using data to establish identity might actually help the Taliban achieve its own version of identity dominance. “That would be the fear of what the Taliban is doing,” she says.

Ultimately, some experts say the fact that Afghan government databases were not very interoperable may actually be a saving grace if the Taliban do try to use the data. “I suspect that the APPS still doesn’t work that well, which is probably a good thing in light of recent events,” said Dan Grazier, a veteran who works at watchdog group the Project on Government Oversight, by email.

But for those connected to the APPS database, who may now find themselves or their family members hunted by the Taliban, it’s less irony and more betrayal.

“The Afghan military trusted their international partners, including and led by the US, to build a system like this,” says one of the individuals familiar with the system. “And now that database is going to be used as the [new] government’s weapon.”

This article has been updated with comment from the Department of Defense. In a previous version of this article, one source indicated that there was no deletion or data retention policy; he has since clarified that he was not aware of such a policy. The story has been updated to reflect this. “

WSJ: In Leaving Afghanistan, U.S. Reshuffles Global Power Relations

https://www.wsj.com/articles/afghanistan-u-s-withdrawal-china-russia-power-relations-11630421715

In Leaving Afghanistan, U.S. Reshuffles Global Power Relations

The American withdrawal creates new complications for China and Russia

After Afghanistan’s U.S.-backed government collapsed on Aug. 15, Beijing couldn’t contain its glee at what it described as the humiliation of its main global rival—even though Washington said a big reason for withdrawal was its decision to focus more resources on China.

In a briefing, Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying highlighted the death of Zaki Anwari, a 17-year-old Afghan soccer player who fell from the landing gear of an American C-17 as it took off from Kabul airport. “American myth down,” she said. “More and more people are awakening.”

In Russia, too, state media overflowed with schadenfreude, albeit tempered by concern about the Afghan debacle’s spillover into its fragile Central Asian allies. “The moral of the story is: don’t help the Stars and Stripes,” tweeted Margarita Simonyan, editor in chief of Russia’s RT broadcaster. “They’ll just hump you and dump you.”

But now that America’s 20-year Afghan war has come to an end, the gloating is turning to a more sober view of how the war and the withdrawal will affect the global balance of power.

The stunning meltdown of the U.S.’s Afghan client state marked the limits of American hard power. The dramatic scenes of despair in Kabul have frustrated and angered many American allies, particularly in Europe, inflicting considerable reputational damage.

Yet despite their propaganda trumpeting the narrative of America’s weakness, it doesn’t appear to have escaped Beijing and Moscow that the U.S. isn’t the only one losing out.

In terms of raw military strength and economic resources, the U.S. remains dominant. Its pivot away from Afghanistan means Washington has more resources to put toward its strategic rivalry with China and Russia, two nations that want to redraw an international order that has benefited American interests and those of its allies for decades.

And unlike Russia and China, countries in Afghanistan’s immediate neighborhood, America is far more removed from the direct consequences of the Taliban takeover, from refugee flows to terrorism to the drug trade. Managing Afghanistan from now on is increasingly a problem for Moscow and Beijing, and their regional allies.

“The chaotic and sudden withdrawal of American forces from Afghanistan is not good news for China,” said Ma Xiaolin, an international relations scholar at Zhejiang International Studies University in Hangzhou, China, noting that America is still stronger in technology, manufacturing and in military power. “China is not ready to replace the U.S. in the region.”

In a phone call with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken on Sunday, China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, said the U.S. needed to remain involved in Afghanistan, including by helping the country to maintain stability and combat terrorism and violence, according to a statement on the Chinese foreign ministry’s website.

Moscow, too, urged the U.S. and allies not to turn away. Zamir Kabulov, President Vladimir Putin’s special envoy for Afghanistan, said Western countries should reopen embassies in Kabul and engage in talks with the Taliban on rebuilding the country’s economy. “This applies first of all to those nations that remained there with their armies for 20 years and caused the havoc that we see now,” Mr. Kabulov told Russian TV.

Chinese scholars who advise the government expect the U.S. to refocus military resources on countering Beijing, especially in the Western Pacific, and to show greater resolve in an area whose strategic importance is now a rare point of bipartisan consensus.

President Biden, in his April speech announcing the withdrawal from Afghanistan, after a war that cost hundreds of billions of dollars and took 2,465 American lives, justified the move by highlighting this imperative: “Rather than return to war with the Taliban, we have to focus on the challenges that are in front of us,” he said. “We have to shore up American competitiveness to meet the stiff competition we’re facing from an increasingly assertive China.”

Policy move

The U.S. could have enabled the Afghan republic to stave off the Taliban for years, if not decades, by continuing a relatively small U.S. military presence, focused on air support, intelligence and logistics rather than ground combat. Instead of a military defeat, like in 1970s Vietnam, the American withdrawal was a deliberate policy move, even if it caused unintended consequences.

“Serious people in Moscow understand that the American military machine and all the components of America’s global superiority are not going anywhere, and that the whole idea of no longer being involved in this ‘forever war’ was a correct one,” said Alexander Gabuev, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Moscow Center. “Yes, the execution was monstrous, but the desire to focus resources on priority areas, especially East Asia and China, is causing here a certain unease, a disquiet—and an understanding of the strategic logic.”

The main hope in Moscow, he added, is that the fallout from the Kabul withdrawal will lead to further political polarization inside the U.S., and to new strains in ties between America and its allies.

These strains are already real, especially after Mr. Biden rebuffed European requests to extend the Aug. 31 withdrawal deadline so that allies would be able to airlift their remaining citizens and Afghans allies out of Kabul. Tens of thousands of such people, eligible for evacuation, remain stranded.

Even the closest of America’s allies, such as the U.K., have openly criticized the U.S. withdrawal. Tom Tugendhat, chairman of the foreign-affairs committee in the U.K. House of Commons and an Afghanistan war veteran, compared the debacle in Kabul to the 1956 Suez crisis, which bared the limits of British power and precipitated his nation’s strategic retreat.

“In 1956, we all knew that the British Empire was over but the Suez crisis made it absolutely clear. Since President Obama, the action has been of U.S. withdrawal, but my God, has this made it clear,” Mr. Tugendhat said in an interview.

That’s not necessarily great news for Russia and China, he added.

“The reality is that Chinese and Russian bad behavior is only possible in a world that is U.S.-organized,” Mr. Tugendhat said. “You can only be an angry teenager if you know that your dad is still going to put petrol in the car the next day.”

The U.S. denouement in Afghanistan has raised particular concerns in Taiwan, the democratic island Beijing seeks to unite with the mainland—by force if necessary. The U.S. is obliged by law to help Taiwan defend itself. After pro-Beijing politicians warned that Taiwan shouldn’t depend on U.S. assistance in the event of a Chinese assault, Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen issued a statement calling for the island to be more self-reliant.

The prevailing view among U.S. allies and partners in Asia is that Washington can now deliver, finally, on the “pivot to Asia” that the Obama administration promised as a way to counter China but largely failed to deliver as it was preoccupied with Afghanistan and the Middle East.

“There’s an acknowledgment of lessons that need to be learned,” said S. Paul Choi, a former South Korean army officer and adviser to U.S. forces there who is now a Seoul-based security consultant. “On a more positive note, what Asian allies would like to see is greater attention, greater human resources, greater training of personnel…that focuses more on this region rather than, say, counterterrorism in the Middle East.”

White House spokeswoman Jen Psaki earlier this month challenged the notion that the events in Kabul create an opening for Moscow or Beijing to test America’s will in their own neighborhoods. “Our message is very clear: We stand by, as is outlined in the Taiwan Relations Agreement, by individuals in Taiwan,” she said. “We stand by partners around the world who are subject to this kind of propaganda that Russia and China are projecting. And we’re going to continue to deliver on those words with actions.”

While the chaos in Afghanistan has at least temporarily undermined America’s credibility with partners and allies, these relationships, from Taiwan to Israel to Ukraine, are based on a unique set of commitments—and, unlike America’s Afghan venture, don’t have a preset expiration date. Washington broadcast its intention to leave Afghanistan since President Obama’s first term more than a decade ago, although many Afghan leaders believed it would never actually do so.

Slawomir Debski, director of the Polish Institute of International Affairs, an influential Warsaw think tank, said that the trouble in Kabul will have little effect where it matters for his nation: America’s and NATO’s ability to deter Russia on the alliance’s eastern flank.

“Nobody among the allies criticized the Biden administration for the withdrawal decision itself. They criticized its miserable execution,” he said. “But this doesn’t change the fundamental relationship. Our alliance with the Americans is long enough for us to know that they make mistakes that are easily avoidable.”

Terrorism

The U.S. invaded Afghanistan in 2001 because the country’s Taliban rulers at the time hosted Osama bin Laden and other al Qaeda leaders who plotted the Sept. 11 attacks on America. Since then, Islamist terrorist groups, particularly the far more radical Islamic State, have established other footholds around the world, from Mozambique to the Philippines to West Africa.

Afghanistan, where Islamic State carried out Thursday’s Kabul airport bombing that killed 200 Afghans and 13 U.S. troops, shares a small stretch of mountainous border with China and a lengthy, porous frontier with Tajikistan and other Central Asian states that send millions of migrant workers to Russia.

During recent visits to Russia and China, Taliban leaders have assured their hosts that they won’t allow international terrorists to operate from Afghanistan again.

“The Taliban say all the right words for now: They will not allow the use of their territory for terrorist activities toward the east, in Xinjiang, or toward the north, in Central Asia,” said Andrey Kortunov, director-general of the Russian International Affairs Council, a Moscow think tank that advises the government. “But so far these are just words.…There are a lot more questions than answers.”

For China, the key issue in Afghanistan has long been the presence of Uyghur militants from the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, or ETIM, and its successor, the Turkestan Islamic Party. The United Nations has estimated that some 500 of these Uyghur militants are in Afghanistan, mostly in the northeastern Badakhshan province.

Haneef Atmar, the foreign minister of the fallen Afghan republic, said in an interview in early August that the deployment of these Uyghur militants, some of whom have returned to Afghanistan from battlefields in Syria, were one of the reasons that explained the Taliban’s lightning offensive in the north of the country. The Taliban spokesman, Suhail Shaheen, and other senior officials have repeatedly said that the Taliban won’t interfere in China’s internal affairs.

Mr. Wang, the foreign minister, raised the issue directly with Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, the head of the Taliban’s political office, when the two met in China at the end of July. After that meeting, China said it had made clear its demands, pressing the Taliban to break with all terrorist organizations and take resolute action against ETIM.

While eager to succeed where the U.S. failed, Beijing is reluctant to become embroiled in Afghanistan’s domestic politics or to take on the burden of subsidizing the bankrupt Afghan state indefinitely. China’s military lacks experience beyond Chinese borders.

Moscow, with its own painful history in Afghanistan, is also treading carefully. “Afghanistan is a unique place,” said Fyodor Lukyanov, head of Russia’s Council on Foreign and Defense Policy. “It has shown throughout history that great games there bring no benefit to anyone.”

Wang Huiyao, president of the Center for China and Globalization, a Beijing-based think tank, and a counselor to China’s State Council, brought up the example of Vietnam, once the site of America’s humiliating military defeat and now one of Washington’s key partners in Asia.

“It was the same story with the U.S. withdrawal from South Vietnam in 1975: People said it will be taken over by China or the Russians,” said Mr. Wang. “Look at it now.”

Propoganda expert warnings.

Renowned propaganda expert: Worst is still to come in global psy op if people do not rise up and resist

This is a good article that brings up a number of points that I have tracked and agree with over the last year and a half. It’s not a blanket endorsement and there are some nuanced disagreements I have here and there.

As a Christian I know the real endgame to this is ultimately Revelation 13. I’m also not optimistic that enough people are going to “rise and resist” or what that even really means realistically (key word). I would love to be proven wrong but ideally I really hope God intervenes ASAP because I think it’s that far gone and especially when you are talking about an entire planet.

I am posting this here like this because of thought police. Take it for what it’s worth and do your own research past that.

“We need you to give us two weeks to flatten the curve.” How are we doing?

I don’t know how many open lies, contradictions, logic failures, and goal posts being moved people have to see to finally get the picture that something doesn’t add up.

More: https://accountabilityinitiative.org/josh-geltzer-bidens-maga-hunter/

https://www.intellectualtakeout.org/article/orwell-history-stopped-1936-and-everything-propaganda/

https://jrnyquist.blog/2021/07/22/absolute-sabotage-the-rise-and-coming-fall-of-a-false-narrative/ This goes to a different subject but definitely related so far as effects of propoganda, Hegelian Dialectic, and people being dupes unwittingly or not. I think this write up is a lot closer to actual reality.

WSJ: If war comes, will navy be prepared?

https://www.wsj.com/articles/if-war-comes-will-the-u-s-navy-be-prepared-11626041901

f War Comes, Will the U.S. Navy Be Prepared?

A new report details a culture of bureaucracy and risk-aversion that is corroding readiness.

By Kate Bachelder OdellUpdated July 12, 2021 2:42 pm ET

Is the U.S. Navy ready for war? A new report prepared by Marine Lt. Gen. Robert Schmidle and Rear Adm. Mark Montgomery, both retired, for members of Congress paints a portrait of the Navy as an institution adrift. The report, first reported by the Journal and commissioned by Sen. Tom Cotton, Reps. Mike Gallagher, Dan Crenshaw and Jim Banks, concludes that the surface Navy is not focused on preparing for war and is weathering a crisis in leadership and culture.

The impetus for the report was a series of recent catastrophes—a ship burning in San Diego last year; two destroyer collisions in the Pacific in 2017. Were these isolated events? Or did they indicate “larger institutional issues that are degrading the performance of the entire naval surface force”? The report surveyed active and recently retired service members of various ranks, conducting 77 candid hourlong interviews. A key finding: “Many sailors found their leadership distracted, captive to bureaucratic excess, and rewarded for the successful execution of administrative functions” rather than core competencies of war.

“I guarantee you every unit in the Navy is up to speed on their diversity training,” said one recently retired senior enlisted leader. “I’m sorry that I can’t say the same of their ship-handling training.”

Adm. Montgomery told me in an interview over the weekend that when he was a junior officer in the 1980s there was “an intense focus” on a likely confrontation with the Soviet navy—learning about classes of ships or the missiles aboard. After decades without a peer adversary at sea, “the same focus is not permeating the Navy today.”

The Navy has improved its pipeline for surface-warfare officers since the 2017 collisions, reversing a 2003 money-saving mistake of training junior officers by giving them 23 compact discs loaded with reading material. But the Navy doesn’t spend the money and time training surface warfare officers that it does submariners or aviators, and has revamped training so many times, usually in an effort to spend even less money, that commanding officers are left with “inconsistent, often ill-prepared wardrooms.”

Civilian Pentagon appointees of both parties have been poor stewards of the surface Navy’s capabilities. The report estimates that 20 ships a year are extended on deployment, and keeping them at sea creates “a host of problems.” The ship is late to postdeployment maintenance, which can mess up the yard’s schedule for work on other ships. Longer deployments tend to mean more repairs, and delays can cut into training time.

The report also details a deep culture of risk aversion: If the missiles start flying, will a destroyer captain be ready to make quick decisions and take calculated risks, even if his communications are jammed and he can’t reach his superiors?

Historically, ship captains couldn’t reach the higher-ups while at sea and had to make decisions on their own. The price of absolute authority was “the cruel business of accountability,” as a 1952 editorial in this newspaper called it. Now admirals can micromanage “from the comfort of terrestrial headquarters,” as the report puts it. A ship captain quoted in the report recalled his experience of escorting ships through the Strait of Hormuz. “Every single time I knew in the back of my head” that admirals “were literally watching the cameras on my ship second-guessing every single thing I did.”OPINION: POTOMAC WATCHJoe Biden Defends His Afghanistan Pullout00:001xSUBSCRIBE

Commanders have less authority but brutal accountability. In the report, sailors expressed “near universal disdain” for a “one mistake Navy” that defenestrates leaders who make an error. It’s a “drag on retention, lethality and morale.” Former Navy Secretary John Lehman ticks off in the report the five-star admirals who won World War II and their mistakes: Bill Halsey “was constantly getting in trouble for bending the rules or drinking too much”; Chester Nimitz “put his first command on the rocks”; Ernie King was “a womanizer.” They were punished at times, but Navy leadership always realized “these were very, very promising” officers. None, he concludes, could have made it past captain in today’s Navy.

Note also an illustration that captured this mentality in practice from a recent piece in Proceedings magazine. During an overseas exercise (the article doesn’t say when), a U.S. destroyer and a British frigate “traded some paint,” a minor run-in. “The next day at a gunnery exercise, the British ship was on the gun line, and the U.S. ship was headed to port to embark the investigation team.”

Then there is the unhealthy fear of bad publicity. After negative news stories, the report found, “the senior ranks are perceived as quick to sacrifice junior personnel” to save their own tails. Discipline is “bent to the unsteady whims of public perception, not the Navy’s own standards and regulations.”

A command master chief told sailors to “clap like we’re at a strip club” when Vice President Mike Pence came aboard the carrier. He resigned, his 30-year career ending after one misjudgment. Admirals “hide in foxholes at the first sight of Military.com and the Military Times,” said one intelligence officer.

China will be the big topic when Carlos Del Toro, President Biden’s nominee for Navy secretary, appears before the Senate Armed Services Committee on Tuesday. Perhaps Mr. Del Toro, a former destroyer captain, can shake the Navy awake. As the new report notes in closing, there isn’t much time for learning once war is under way.

Mrs. Odell is an editorial writer for the Journal.

WSJ: Search for Covid’s Origins Leads to China’s Wild Animal Farms

https://www.wsj.com/articles/covid-origins-china-wild-animal-farms-pandemic-source-11625060088

XISHUANGBANNA, China—A crucial next step in the hunt for Covid-19’s origins is to examine farms that supplied wild animals to the market where many early cases were found.

There’s one big problem: Almost all the animals are gone.

Farmers who bred or trapped wild animals for food, fur or traditional medicine in China, including in a hilly region near the border with Laos and Myanmar, say they killed, sold or released their stock after Chinese officials ordered them early last year to stop their trade.

“The government bought them up and had them all killed,” said Yang Bo, a 40-year-old farmer in China’s southwestern province of Yunnan. He used to breed about 1,000 bamboo rats a year, selling them for 120 yuan, or about $19, a kilo. “We had to let all our workers go.”

His farm is in Yongde county, where a World Health Organization-led team says one supplier provided bamboo rats to the Huanan food market in Wuhan, site of the first known cluster of Covid-19. Mr. Yang said he didn’t supply animals to the market.

Scientists say the closing of operations like Mr. Yang’s made sense as a precaution to stop the virus from spreading, but should be done only after thorough testing of animals and workers. If such research occurred, it hasn’t been made public. Now, the shutdown is complicating the search for the pandemic’s source and compounding mistrust between China and much of the democratic world.

The closures made it much harder—perhaps even impossible—to establish whether the Covid-19 virus, which is thought to have originated in bats, spread to humans via another species, according to members of the WHO-led team and other leading scientists around the world.

The lack of progress in finding an animal source for the virus also is helping fuel interest in an alternative explanation: that the virus could have spilled from the Wuhan Institute of Virology or another laboratory in the city.

The WHO-led team and many other scientists say a natural viral jump from an animal to a human remains the most plausible hypothesis, and a recent study has shown that wild animals susceptible to the virus were sold live at markets in Wuhan. That makes it important to test former wildlife farmers and their contacts for antibodies, to determine whether they were infected, and to learn more about how they handled their stock, the scientists say.

Time is running out, though, because antibody levels fade.

Evidence of infection in farmworkers will be a lot harder to find after two or three years, Peter Daszak, a zoologist on the WHO-led team, said in an interview with The Wall Street Journal earlier this year.

“There’s a lot more that needs to be done,” said Dr. Daszak, whose organization has worked with the Wuhan Institute of Virology and who has rejected the lab-leak hypothesis. “Doing further trace back to those farms is critical, and hasn’t been done to the level we really need it to be done to say definitively this is or is not the pathway,” he said.

He and other scientists say the main reason for the farm closures appeared to be to protect the public. They took place when the priority was to stop the virus from spreading, and after Chinese officials had announced that it most likely came from wild meat at a Wuhan market. Scientists who have studied the earliest known cases say the market may have been the site of a superspreading event rather than where the virus first spread to humans, since many early cases had no link to it.

At this stage, however, the closures, coupled with the disinfection of the market and the failure to test wildlife farmers earlier, have hampered the search for an animal that might have been the virus’s intermediate host between bats and humans. Some scientists doubt that further screening around former wildlife farms will reveal much.

“It will hardly be possible to make any progress here” without animal samples from potential intermediate hosts taken at the time of the first Covid-19 cases, said Martin Beer, a virologist at Germany’s leading animal-disease center, the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut. “Current tests would not provide any useful information,” he said, because they wouldn’t show whether a positive case was infected by an animal or another human, or if it was the original variant.

Maureen Miller, an epidemiologist at Columbia University, said animal testing should have been done early to identify which species might have first infected a human. “It happened probably so long ago that we’ll never know which animal it was,” she said.

She and other emerging-disease specialists said it wasn’t clear whether Chinese researchers had done additional wildlife testing beyond what they have made public. “I do not blame China for being the source [of the pandemic],” she said. “I hold them accountable for not sharing the information they have in a timely fashion, if at all.”

China’s National Health Commission didn’t respond to a request for comment. Despite initially pointing to wild meat as the virus’s likely vector, Chinese officials have played that down in recent months and suggested instead that it could have come from outside China and spread via imported frozen food. Beijing denies the virus leaked from a Chinese lab.

Failure to identify the source could make it much harder to stop the virus from spilling again into the human population and to identify ways to prevent similar pathogens from causing future pandemics.

It also risks aggravating tensions between China and many democratic nations, especially the U.S, which want Beijing to allow a more timely, transparent and science-led probe into the virus’s origins.

The WHO-led team concluded after a visit to Wuhan in January and February that the virus most likely originated in bats and spread to humans via another mammal, possibly one sold in the Huanan food market. Traces of the virus were found on stalls and in sewers at the market, which was closed and thoroughly disinfected soon after the first cases were found. None of the animal samples retrieved tested positive.

The team did establish that frozen specimens of animal carcasses included some species that can harbor SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, and that some of the market’s wild meat suppliers were in parts of China that are home to coronavirus-bearing bats.

Of particular interest, they said, were suppliers in Chinese provinces that border Southeast Asia, such as Yunnan.

In a joint report with Chinese experts published in March, the team recommended more extensive testing of wild animals bred for food in such areas, including ferret badgers and civets, or for fur, such as minks and raccoon dogs.

A study published on June 7 provided further clues, revealing that more than 47,000 wild animals were sold in Wuhan markets, including the Huanan one, in the 31 months before December 2019. Most were sold live, often in cramped cages that could allow viruses to jump between species and their human handlers. Among them were at least five species susceptible to SARS-CoV-2—weasels, minks, raccoon dogs, palm civets and Asian badgers.

The study’s authors say they couldn’t share their findings earlier because they were undergoing peer review, but some scientists, including the WHO-led team’s leader, question why the underlying data wasn’t made available much faster.

Around Xishuangbanna, a city in Yunnan province about 30 miles from the cave where scientists found a virus 93.3% similar to SARS-CoV-2, former wildlife farmers said they have either gone back to breeding fish, chicken and duck or switched to other businesses.

“Who would dare to breed such animals now?” said one 42-year-old farmer, who said he used to breed bamboo rats and sell them to local restaurants and food markets. He said he stopped in February 2020 and now works as a builder.

Some 90 miles to the northeast, in an area near a disused mine where scientists found a virus 96.2% similar to SARS-CoV-2, villagers said they stopped breeding wildlife in response to a government campaign around February of last year.

Further west, in Yunnan’s Yongde county, where the WHO-led team said one supplier, which it didn’t name, had provided bamboo rats to the Huanan market, two farmers told the Journal they and other breeders in the area had stopped rearing the animals early last year.

Government notices indicate that similar campaigns were implemented across the country, including in regions in central China that the WHO-led team says provided rabbits and ferret badgers, both of which can carry SARS-CoV-2, to the Huanan market.